By: David Xi-Ken Shi 曦 肯

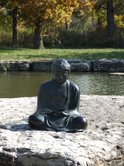

I greatly respect the life experience reflected in the teachings of Master Dogen, especially when I open my mind to what he is pointing at when I get his 13th century language out of the way. This is the challenge that all serious students have when reflecting on what our legacy teachers have transmitted to us. It is the nature of their karma. Master Dogen taught that zazen is the key to our awakening. I bow to his wisdom. But why do I say then that “zazen is not the better way?” This is yet another lesson of when the ideal meets the real. Some Zen teachers may even have said that zazen is not the better way, it is the only way. The problem with this statement is in using the words better or only.

The important point here is for us to understand what zazen really means. Zazen is pointing to our universal natures, or that we are expressions of the universe. The practice of mindful meditation can be a bridge to zazen, just as what we “do” in each moment off the cushion can be a bridge to awakened moments when our body-mind is ready. Zazen is expressed in how we are when we do enough work on the cushion to establish a clear and abiding mind transformation without making unnecessary distinctions, or thinking. I express this as saying that Buddhism is about subtraction not addition. We learn to subtract from our ordinary mind-state so we can become ready to move beyond it to an extra-ordinary mental experience. This can achieve a body-mind state that is natural to our human-beingness. The reality of this universal self is not to run away from either the good or unsatisfactory situations we may encounter in the moment. When we establish a mental attitude of life where our Buddha nature lives from states of reality rather than self imposed notions of a set of ideals, we awaken to acknowledge that a healthy worldview accepts a world just as it is. While ideals may be a part of our worldview platform, they are only blueprints that we take with us into the real world experience. Reality reflects a life lived with varied scenery. These various scenes unfold as they have been driven by the causal-chain of events we are honing in our practice on the cushion. A healthy and harmonious mind accepts things as they are. No better, no bad, no only. It just is when we get ourselves out of the way and move into a mental state capable of “becoming.” This is why I say that zazen is not the better path. The reality of our lives that zazen wakes us up to is really a life that comes from our natural self, and a now that is only the now we can fully trust as being real. Our past experiences, and any thoughts of future expectations, only can prepare us for the present moment. All else is an illusion. When we base our lives on distinguishing between the better way and the worse way, we will never find a peaceful mind that whatever happens is all right. There is no end in looking for “the better.”

Zazen is pointing us to the lessons of interdependence, universal connectiveness, impermanence, and a way of moving away from floundering in desperation. Shikantaza means just sitting and Dogen used both expressions to teach the nature of meditation as a vehicle for transformation beyond the ordinary. However, zazen as Dogen Zenji used it in a broader sense indicates the reality that is manifested in practice. Zazen is about refining how we are. A delineated best path does not exist for universal life. There is only the direction of natural causal forces as they influence our life. This is equally true of zazen as a practice we may choose. So how can it be better, when how we are is our natural state of being all along. We just must come to realize this reality. So zazen is like a mirror too. How we come to see what is reflected is up to our ability to awaken to what is real. “Just like this.”